Quantum Cryptography

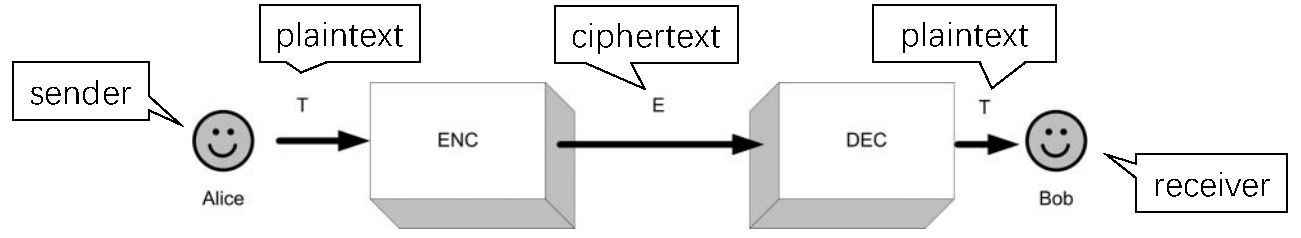

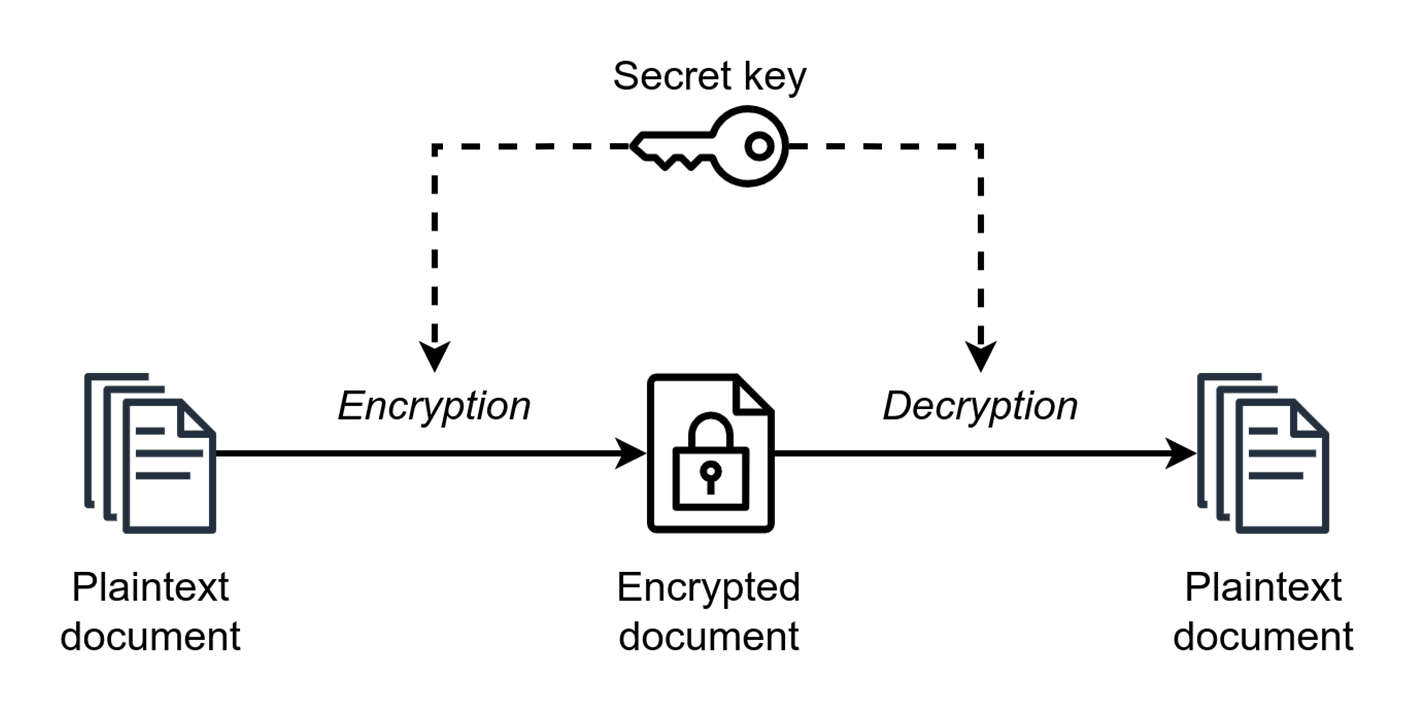

Cryptography is the art of concealing message. The standard cryptography model is shown in Figure [6.1](#fig:cryptography model).

The whole procedure can be divided into two parts:

-

Encoder (ENC) is responsible for encoding the input plaintext into ciphertext, which can be formulated as where is the plaintext, is encryption key, and is the ciphertext.

-

Decoder (DEC) is responsible for decoding the received ciphertext into plaintext, which can be formulated as where is the decryption key.

means that as long as we use the right keys, we can always retrieve the original message intact without any loss of information.

Classic Cryptography

Caesar cipher

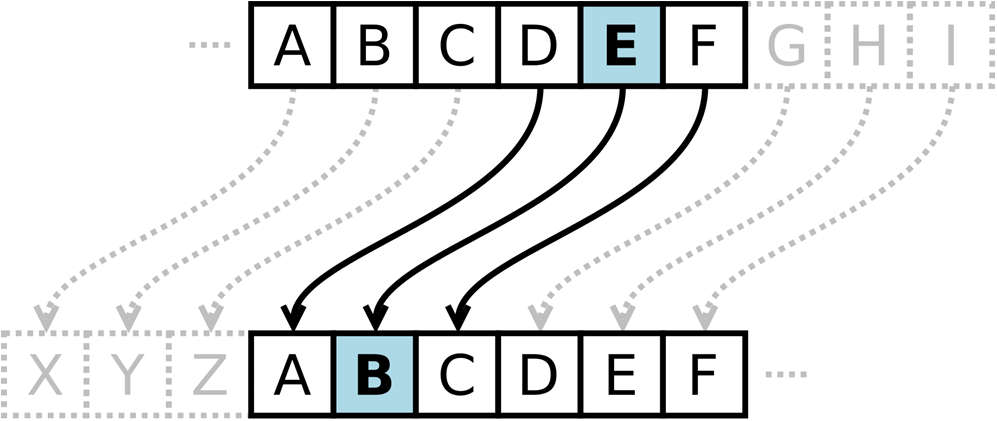

In cryptography, a Caesar cipher1 , also known as Caesar's cipher, the shift cipher, Caesar's code or Caesar shift, is one of the simplest and most widely known encryption techniques. It is a type of substitution cipher in which each letter in the plaintext is replaced by a letter some fixed number of positions down the alphabet. As shown in Figure 6.2, with a left shift of 3, D would be replaced by A, E would become B, and so on. The method is named after Julius Caesar, who used it in his private correspondence.

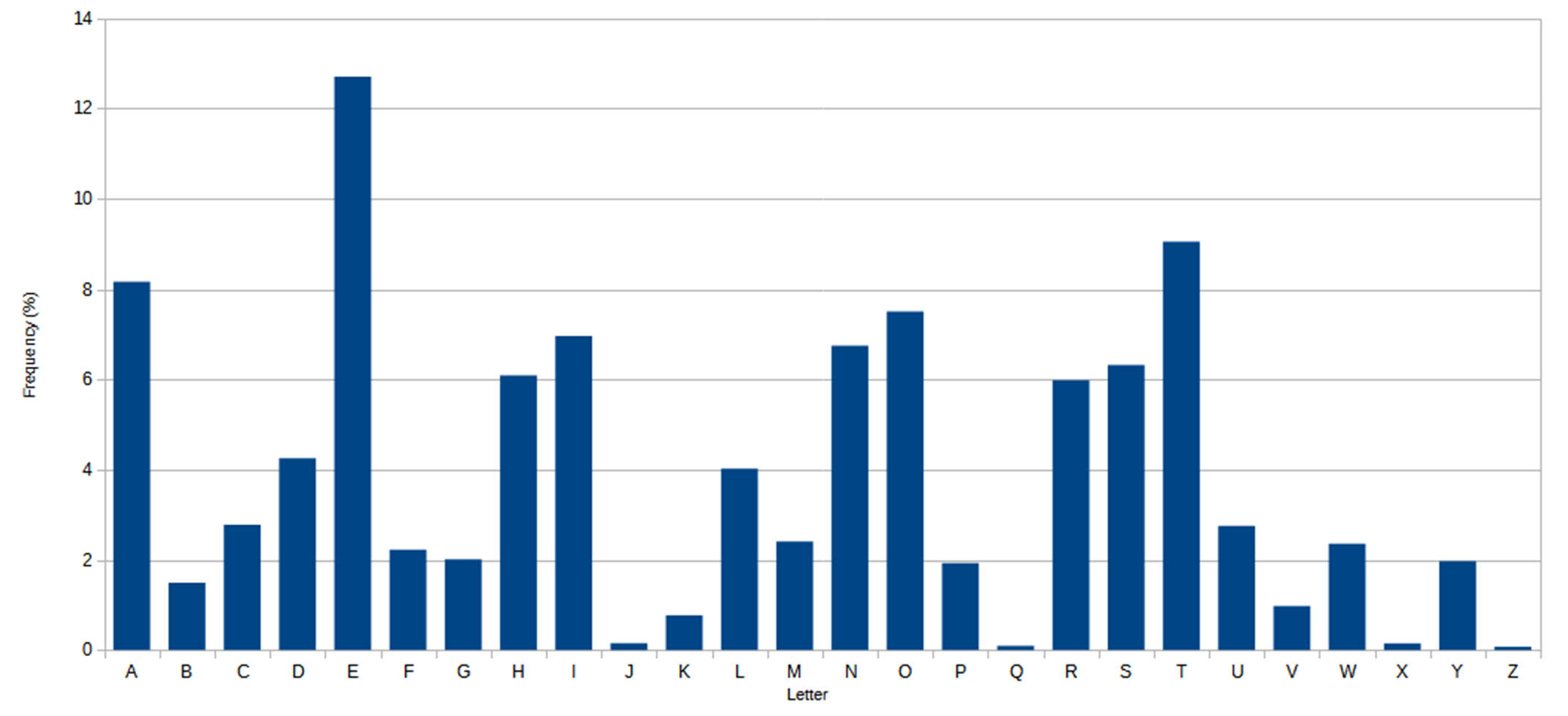

The essence of Caesar cipher is a simple linear mapping, which has high statistical correlation between the letter in plaintext and that in the ciphertext. This means that by graphing the frequencies of letters in the ciphertext, and by knowing the expected distribution of those letters in the original language of the plaintext, a human can easily spot the value of the shift by looking at the displacement of particular features of the graph. This is known as frequency analysis. As shown in Figure 6.2, in the English language the plaintext frequencies of the letters E, T, (usually most frequent), and Q, Z (typically least frequent) are particularly distinctive.

One-Time-Pad protocol

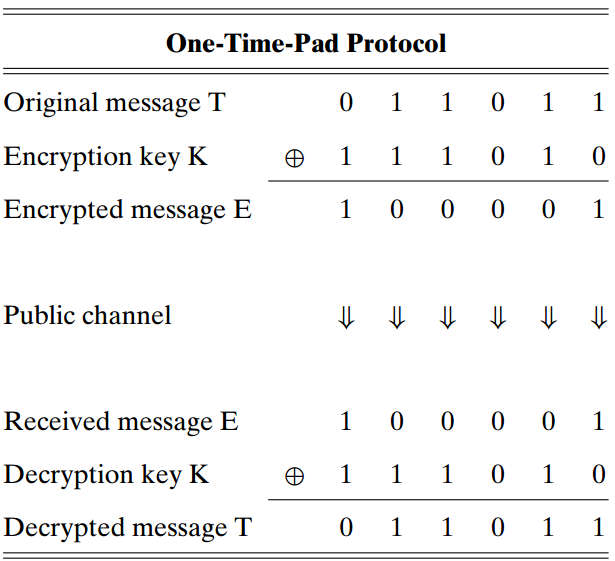

In cryptography, the one-time-pad (OTP) protocol2 is an encryption technique that cannot be cracked, but requires the use of a single-use pre-shared key that is not smaller than the message being sent. In this technique, a plaintext is paired with a random secret key (also referred to as a one-time pad). Then, each bit or character of the plaintext is encrypted by combining it with the corresponding bit or character from the pad using modular addition.

In OTP protocol, both encryption and decryption end share the same key in the communication process, which means . As shown in Figure 6.3, assume that both encoder and decoder share the same working function , than the receiver can decode the ciphertext and get the original message as follows

The merit of OTP protocol is that it cannot be cracked, but meanwhile, it has two obvious drawbacks. First, the key in OTP must be longer than the message being sent, which is extremely inconvenient in the transmission and storage process; Second, the key cannot be re-used because of the risk of information leakage3.

Diffie-Hellman key exchange

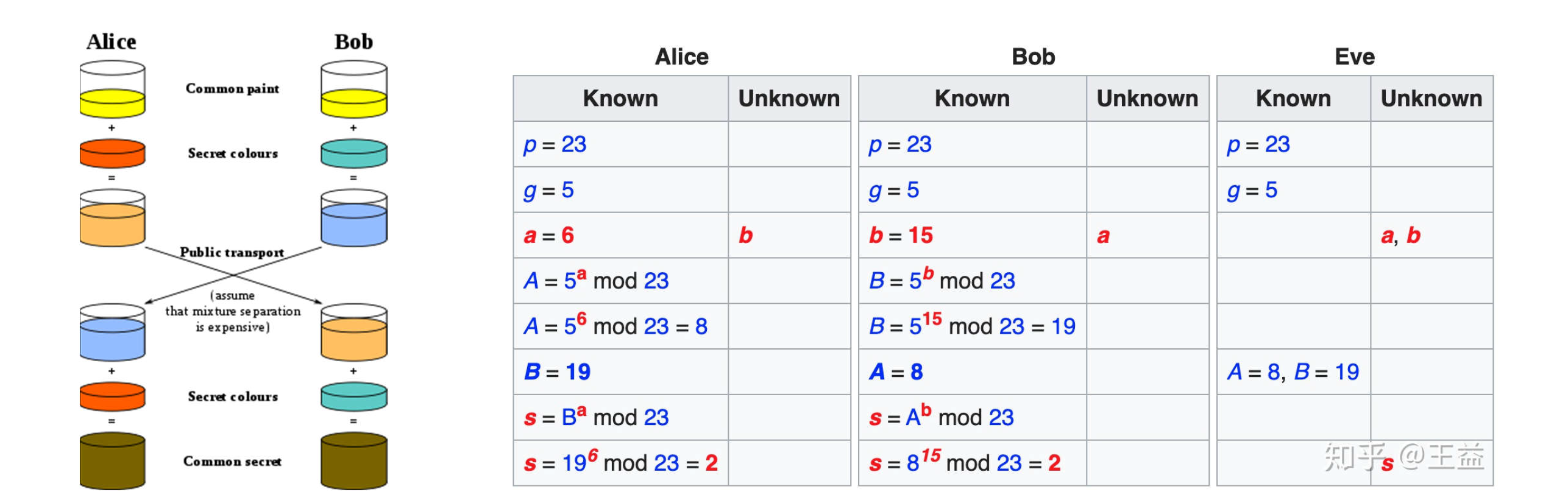

To eliminate risks in the key distribution process, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman devised the Diffie-Hellman key exchange method to securely exchange cryptographic keys over a public channel.

An analogy illustrates the concept of public key exchange by using colors instead of very large numbers. As shown in Figure 6.4, the Diffie-Hellman key exchange process begins by having the two parties, Alice and Bob, publicly agree on an arbitrary starting color that does not need to be kept secret. In this example, the color is yellow. Each person also selects a secret color that they keep to themselves -- in this case, red and cyan. The crucial part of the process is that Alice and Bob each mix their own secret color together with their mutually shared color, resulting in orange-tan and light-blue mixtures respectively, and then publicly exchange the two mixed colors. Finally, each of them mixes the color they received from the partner with their own private color. The result is a final color mixture (yellow-brown in this case) that is identical to their partner's final color mixture.

The numerical example of the above colorization process is shown in Figure 6.4. The pigment mixing process is formulated as a classic trapdoor function, also dubbed as one-way function, i.e., modular exponentiation . The forward computation, from to , is easy and fast, while the backward computation, from to , is extremely hard and computationally prohibitive. In the table, and represent the secret color that Alice and Bob keep to themselves at the beginning, and represent the publicly exchanged color, and is the final shared color mixture. Thanks to the one-way property of the modular exponentiation, even Eve got and , he cannot recover and , not to mention the exchanged key .

Public- and private-key cryptography

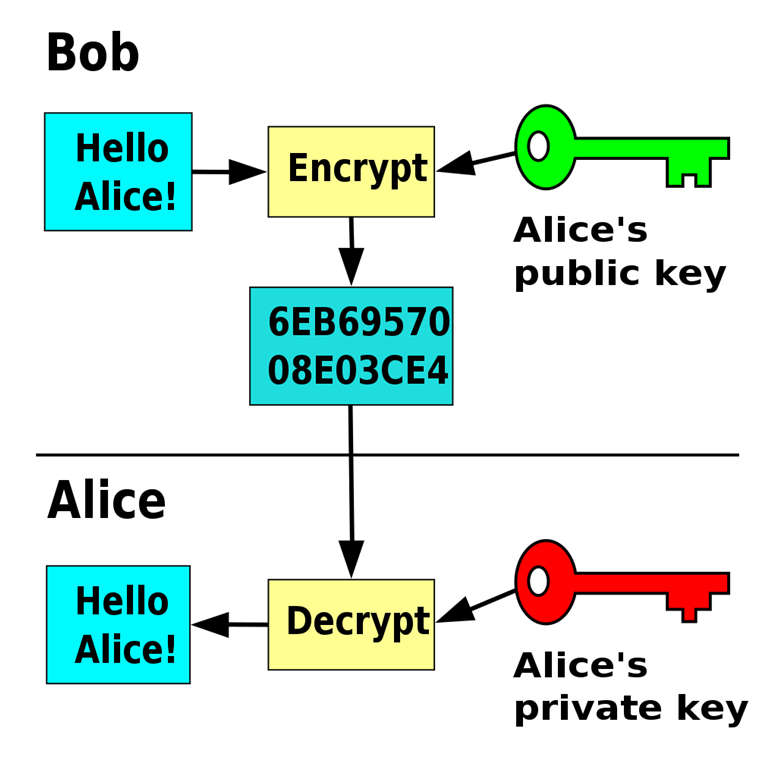

According to the availability of the encryption key, cryptography algorithm can be divided into private-key cryptography and public-key cryptography (Figure 6.5).

private-key cryptography, or symmetric cryptography, uses the same cryptographic keys for both the encryption of plaintext and the decryption of ciphertext. The keys, in practice, represent a shared secret between two or more parties that can be used to maintain a private information link (Figure 6.5). The requirement that both parties have access to the secret key is one of the main drawbacks of symmetric-key encryption, in comparison to public-key encryption. OTP protocal is a typical private-key algorithm.

Public-key cryptography, or asymmetric cryptography, is the field of cryptographic systems that use pairs of related keys. Each key pair consists of a public key and a corresponding private key. Key pairs are generated with cryptographic algorithms based on mathematical problems termed one-way functions. In a public-key encryption system, anyone with a public key can encrypt a message, yielding a ciphertext, but only those who know the corresponding private key can decrypt the ciphertext to obtain the original message (Figure 6.5). Diffie-Hellman key exchange belongs to the public-key cryptography.

The plus side of public-key cryptography is that it does have key distribution problem. In contrast, the minus sides include: (1) the one-way property of trapdoor function is a temporary fact that may disappear in the future; (2) public-key cryptography is usually slower than private-key cryptography.

Typical issues in classic cryptography include: (1) success communication; (2) intrusion detection, i.e., Alice and Bob would like to determine whether Eve is, in fact, eavesdropping; (3) authentication, i.e., we would like to ensure that nobody is impersonating Alice and sending false messages.

Quantum Key Exchange

Due to the peculiar effect of quantum observation and measurement, eavesdropping in the classical world has a very different manifestation from that in the quantum world. Specifically, in the classic world, Eve can make copies of arbitrary portions of the encrypted bit stream, and he can listen without affecting the bit stream. While in the quantum world, Eve cannot make perfect copies of the qubit stream because of the no-cloning theorem, and the very act of measuring the qubit stream alters it.

The BB84 protocol

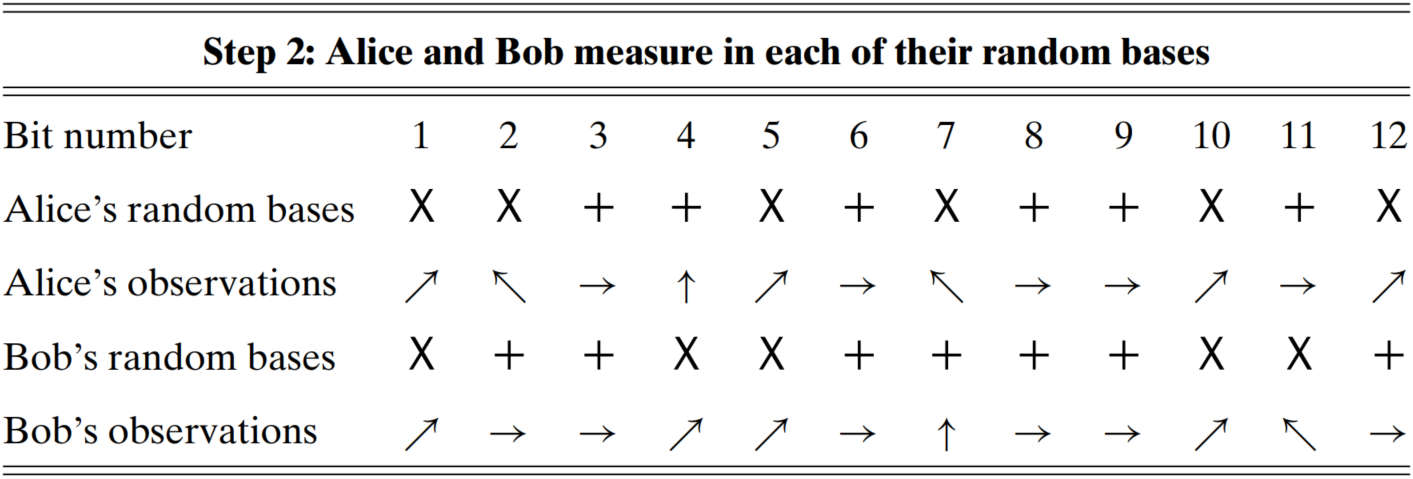

The first quantum key exchange protocol was introduced by Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard in 1984, and hence the name BB84.

Problem setting. Alice's goal is to send Bob a key via a quantum channel. Just as in the One-TimePad protocol, her key is a sequence of random (classical) bits obtained, perhaps, by tossing a coin. Alice will send a qubit each time she generates a new bit of her key. But which qubit should she send?

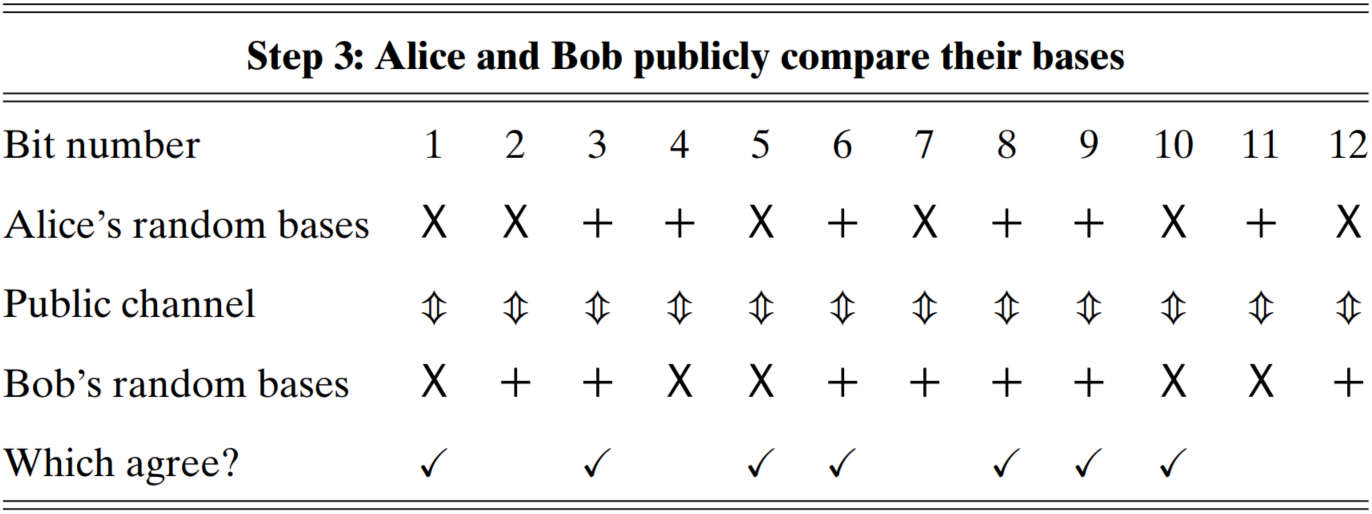

Plus and times bases. In this protocol, Alice will employ two different orthogonal bases shown in Figure 6.6. The left part shows the "plus" basis whose formulation is

and the right part shows the "times" basis whose formulation is

Cross representation. The base vector in one basis can be linearly represented by base vectors in another basis:

-

with respect to will be .

-

with respect to will be .

-

with respect to will be .

-

with respect to will be .

Mapping table. Alice translates her classic key bits into qubits according to a mapping vocabulary shown in the following table.

| State/Basis | ||

|---|---|---|

For example, in the basis, a will correspond to a . If Alice wants to work in the basis and wants to convey a , she will send a . Similarly, if Alice sends a and Bob measures a in the basis, he should record a .

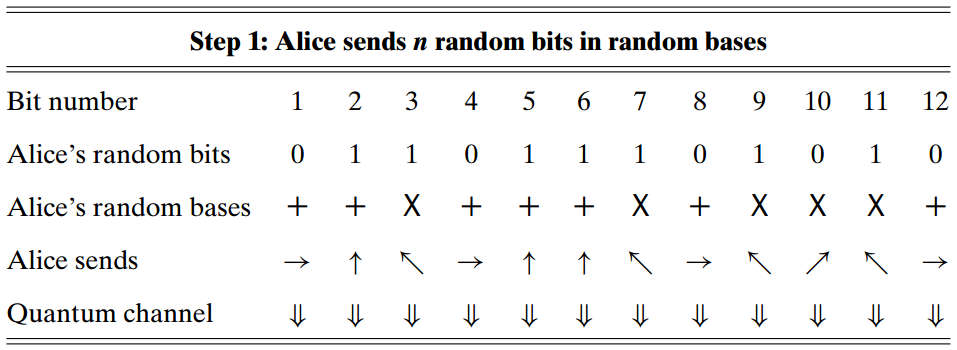

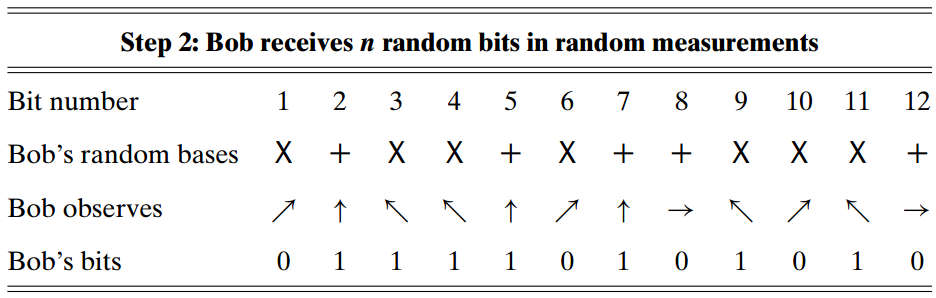

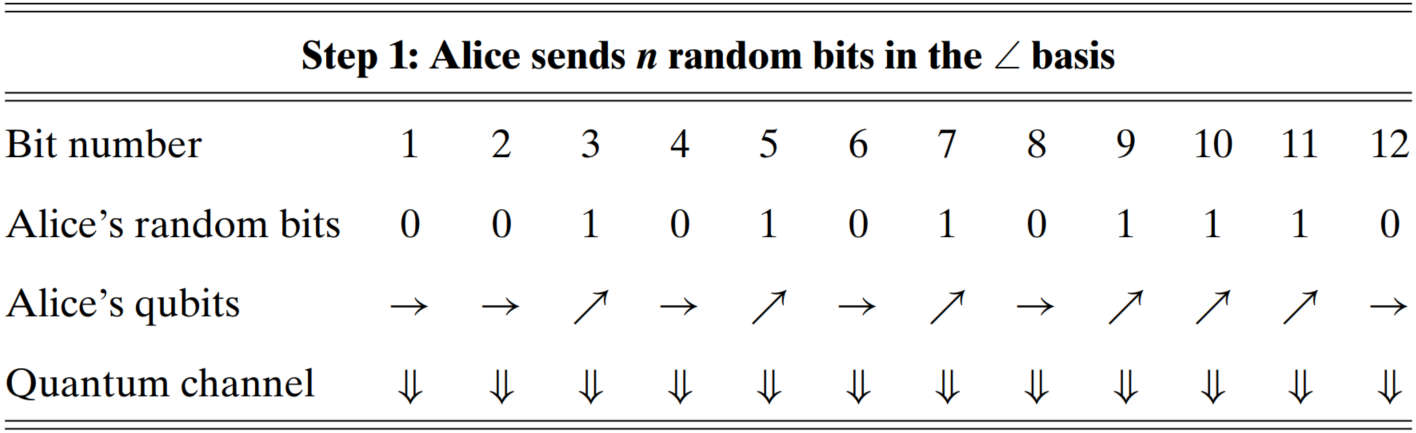

BB84 protocol. There are totally steps in the BB84 protocol:

-

(Alice)

-

randomly determine classical bits to send

-

randomly determine the bases to send bits

-

send the bits in their appropriate basis

-

-

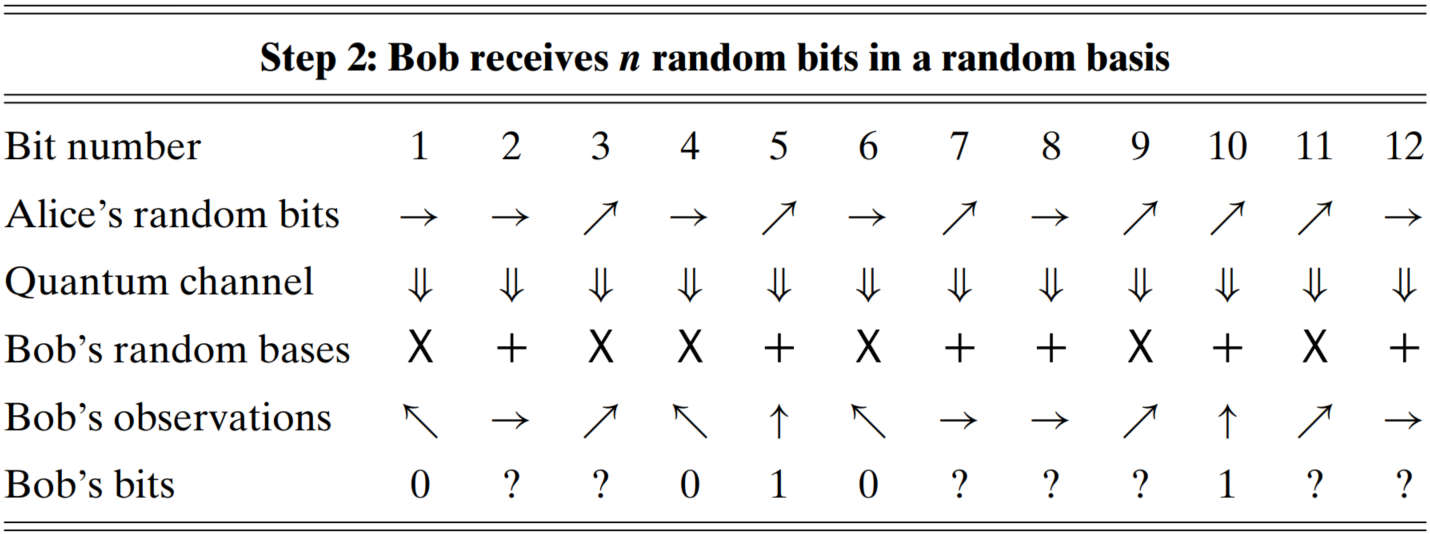

(Bob)

-

randomly determine the bases to receive bits

-

measure the qubit in those random bases

When there is no eavesdropping, Bob has probability to get the correct bit with consistent bases, and probability to get the correct bit with inconsistent bases. Hence the expected correct rate (ECR) for Bob getting the correct bit is .

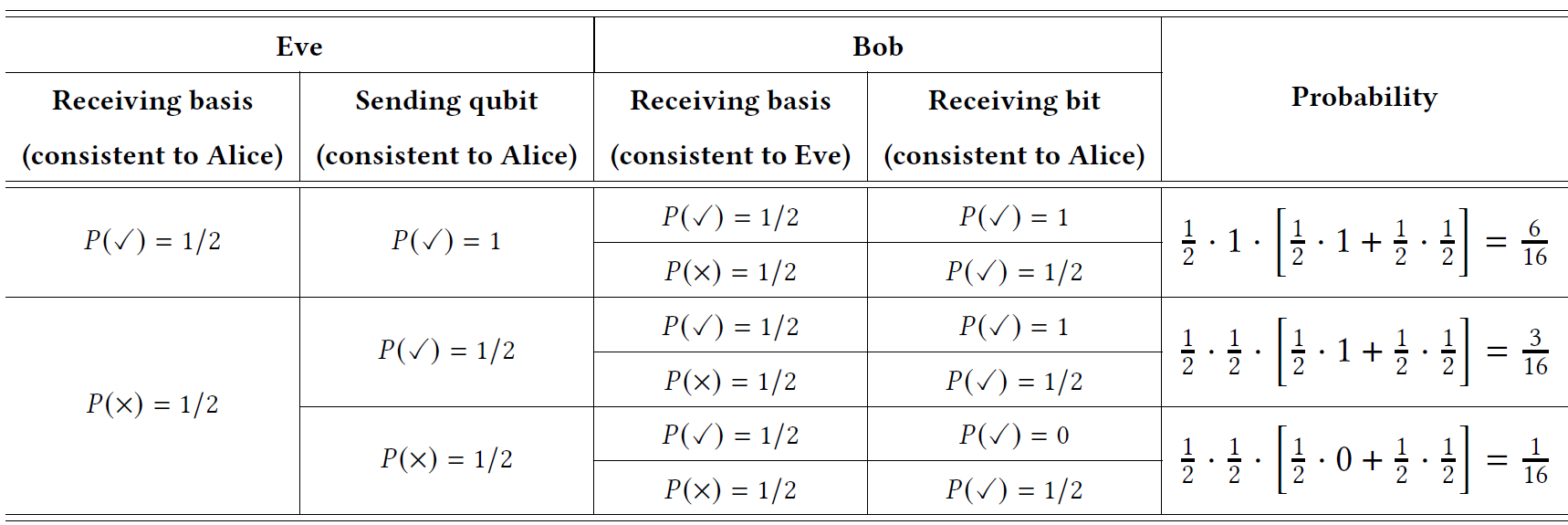

When there is Eve bugging in, he reads the information that Alice transmits, and meanwhile, sneds that information onward to Bob. In this case, ECR changes into . The first term means both Eve and Bob get the correct bit, while the second term represents that Eve gets the wrong bit but Bob gets the right one.

The following Table gives another solution to calculate the ECR with eavesdropping, where the first stage considers the operations of receiving basis and sending qubit of Eve, and the second stage considers the receiving basis and bit of Bob.

-

-

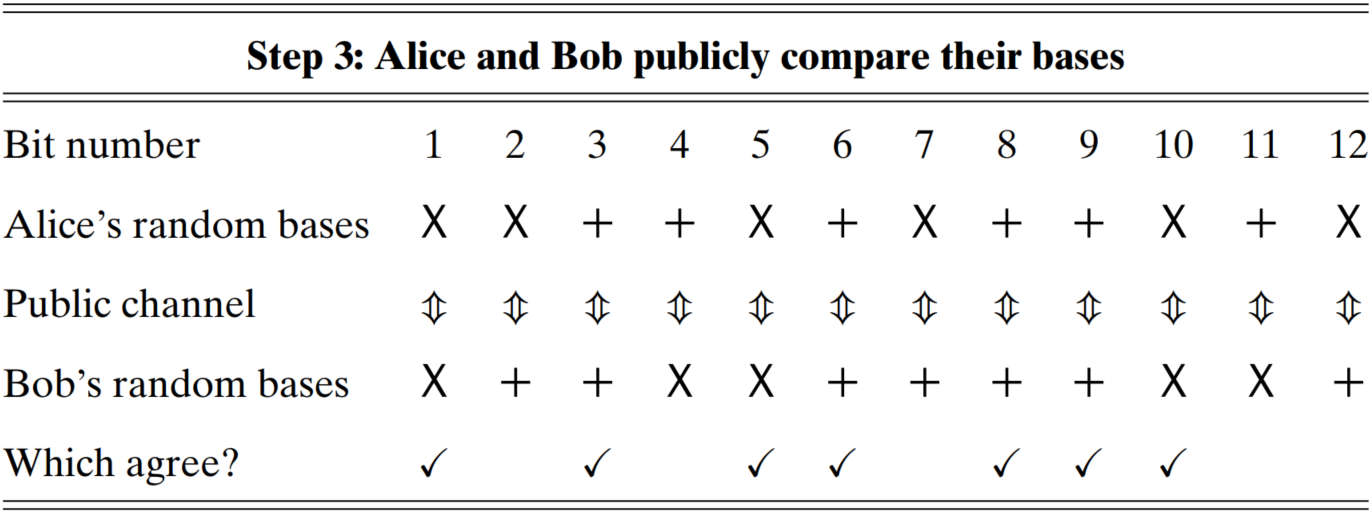

(Alice and Bob)

-

publicly compare which basis they used at each step

-

scratch out corresponding bits under different bases

-

-

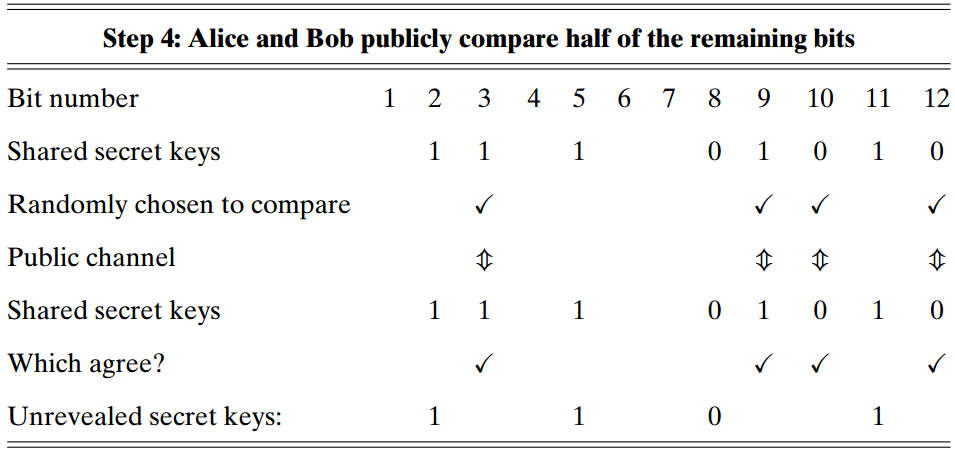

(Bob)

-

randomly chooses half of the bits

-

publicly compares them with Alice

If , Eve is listening, Alice and Bob scratch the whole sequence. Otherwise, Alice and Bob scratch out the revealed test subsequence and keep the remains as unrevealed secret private key.

-

The B92 protocol

In the BB84 protocol, Alice had two distinct orthogonal bases at her disposal. It turns out that the use of two different bases is redundant, provided one employs a slightly slicker means of measuring. This simplification results in another quantum key distribution protocol, known as B92, invented by Charles Bennett in 1992.

The non-orthogonal basis. Alice uses only one non-orthogonal basis

B92 protocol. There are totally steps in the B92 protocol:

-

(Alice)

-

randomly determine classical bits to send

-

send the bits in the appropriate polarization

-

-

(Bob)

-

randomly determine the bases to receive bits

-

measure the qubit in those random bases

-

If Bob uses the basis and observes a , then he knows that Alice must have sent a because if Alice had sent a , Bob would have received a .

-

If Bob uses the basis and observes a , then it is not clear to him which qubit Alice sent. She could have sent a but she could also have sent a that collapsed to a . Because Bob is in doubt, he will omit this bit.

-

If Bob uses the basis and observes a , then he knows that Alice must have sent a because if Alice had sent a , Bob would have received a .

-

If Bob uses the basis and observes a , then it is not clear to him which qubit Alice sent. She could have sent a but she could also have sent a that collapsed to a . Because Bob is in doubt, he will omit this bit.

-

-

(Alice and Bob)

-

Bob publicly tells Alice which bits were uncertain

-

they both omit uncertain bits

-

-

(optional for intrusion detection)

-

Bob randomly chooses half of the bits

-

Bob publicly compares them with Alice

-

The EPR protocol

In 1991, Artur K. Ekert proposed a completely different type of quantum key distribution protocol based on entanglement. In the chapter of composite system, we learned that we can prepare a sequence of entangled pairs of qubits like or . For the discussion convenience, we assume the pair of entangled qubits in the state of .

-

(Alice and Bob)

- Both sides are each assigned one of each of the pairs of entangled qubits

-

(Alice and Bob)

-

separately choose a random sequence of bases

-

measure their qubits in their chosen basis

-

-

(Alice and Bob)

-

publicly compare what bases were used

-

keep only those bits measured in the same basis

-

-

(optional for intrusion or disentangled detection)

-

Bob randomly chooses half of the n/2 bits

-

Bob publicly compares them with Alice

-

Quantum Teleportation

Quantum teleportation is the process by which the state of an arbitrary qubit is transferred from one location to another.

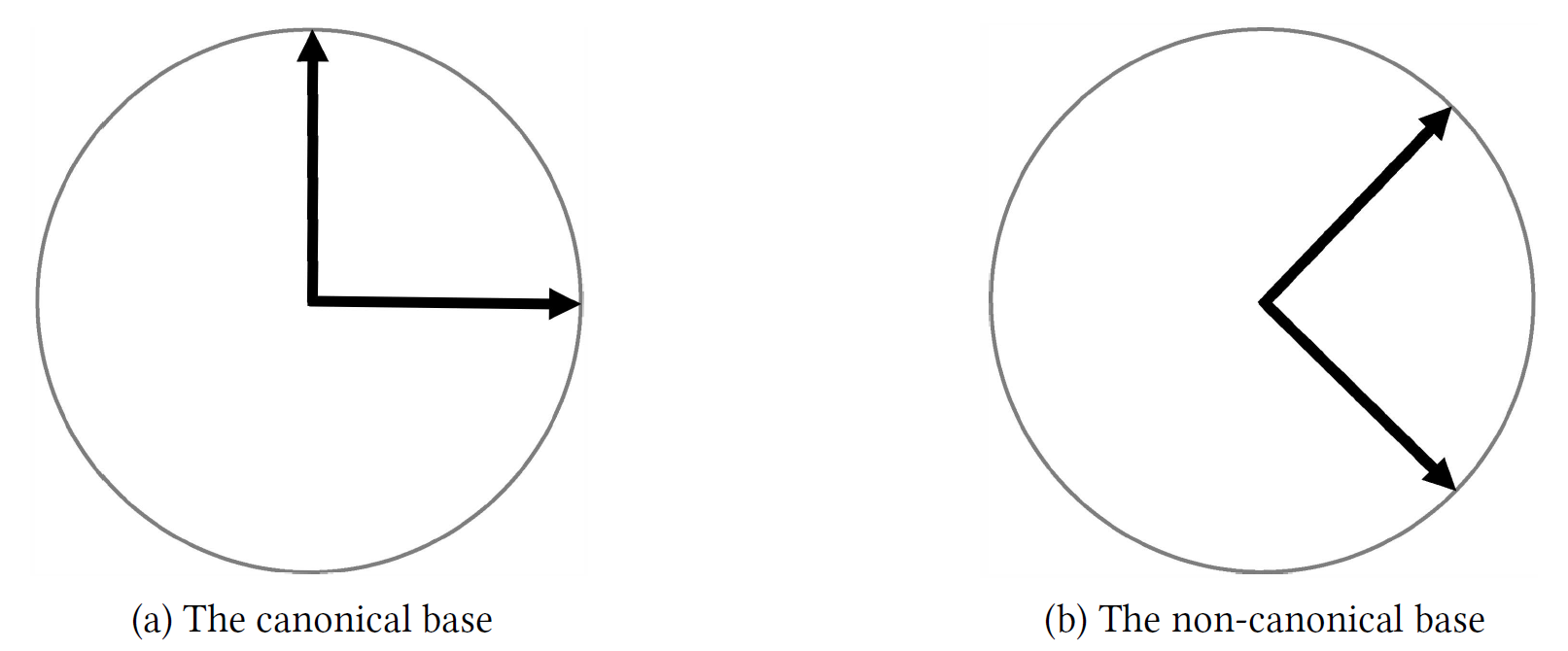

Canonical and non-canonical bases for a single qubit. When working with a single qubit, we worked with the canonical basis, , and non-canonical basis, , as shown in Figure 6.15.

Canonical and non-canonical bases for two qubits. The teleportation algorithm will work with two entangled qubits, one held by Alice and one held by Bob. The obvious canonical basis for this four-dimensional space is: A non-canonical basis, called the Bell basis in honor of John Bell, consists of the following four vectors: Every vector in this basis is entangled.

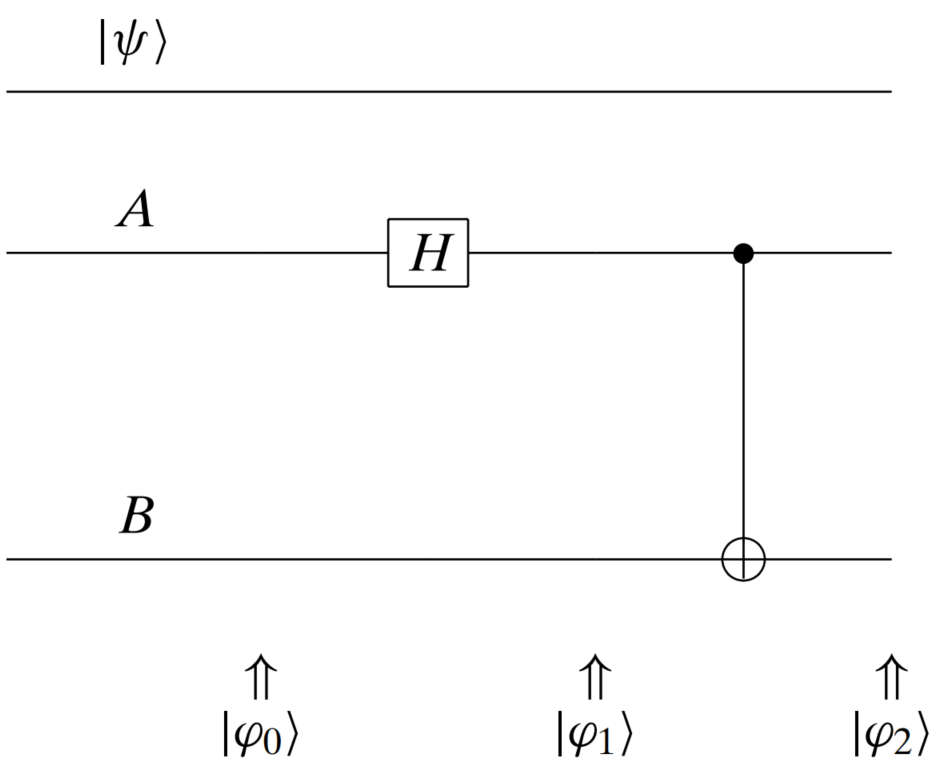

Bell circuit. How to derive the Bell basis? In the single qubit (two-dimensional) case, the elements of the noncanonical basis can be formed using the Hadamard matrix:

In the two qubits (four-dimensional) case, the elements of the non-canonical basis are derived from Bell circuit:

From which, we have , , , .

example:

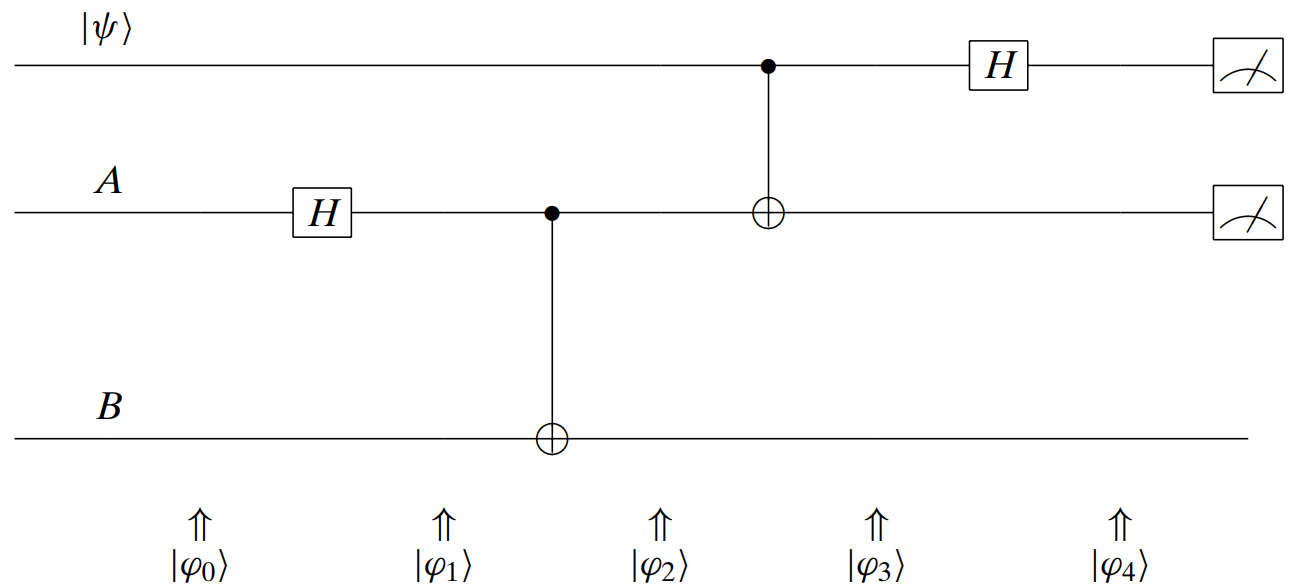

Quantum teleportation protocol. The whole protocol contains steps:

-

: Alice has a qubit .

-

: prepare two entangled quibit A and B

-

two entangled quibits are formed as

-

one is given to Alice and one is given to Bob

-

-

: Alice lets her interact with her entangled qubit

-

: Alice makes a measurement

-

Alice measures her two qubits

-

Alice determines to which of the four possible states the system collapses

-

-

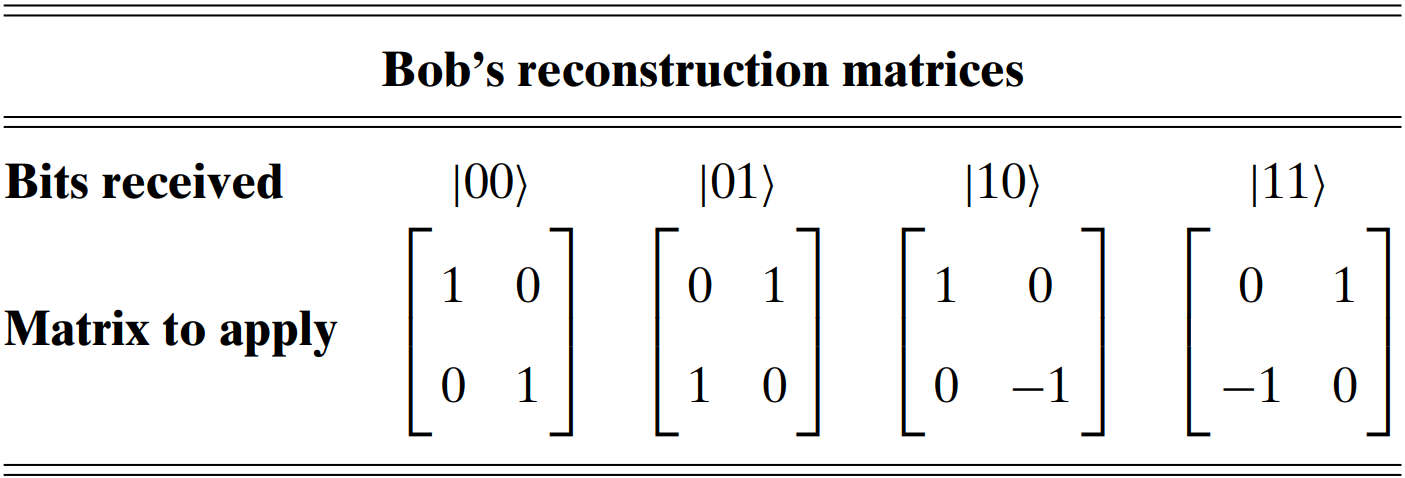

: Bob performs the corresponding transformation based on Alice's observations

-

Alice sends copies of her two bits (not qubits) to Bob

-

Bob uses that information to achieve the desired state

example

exampletransformation:

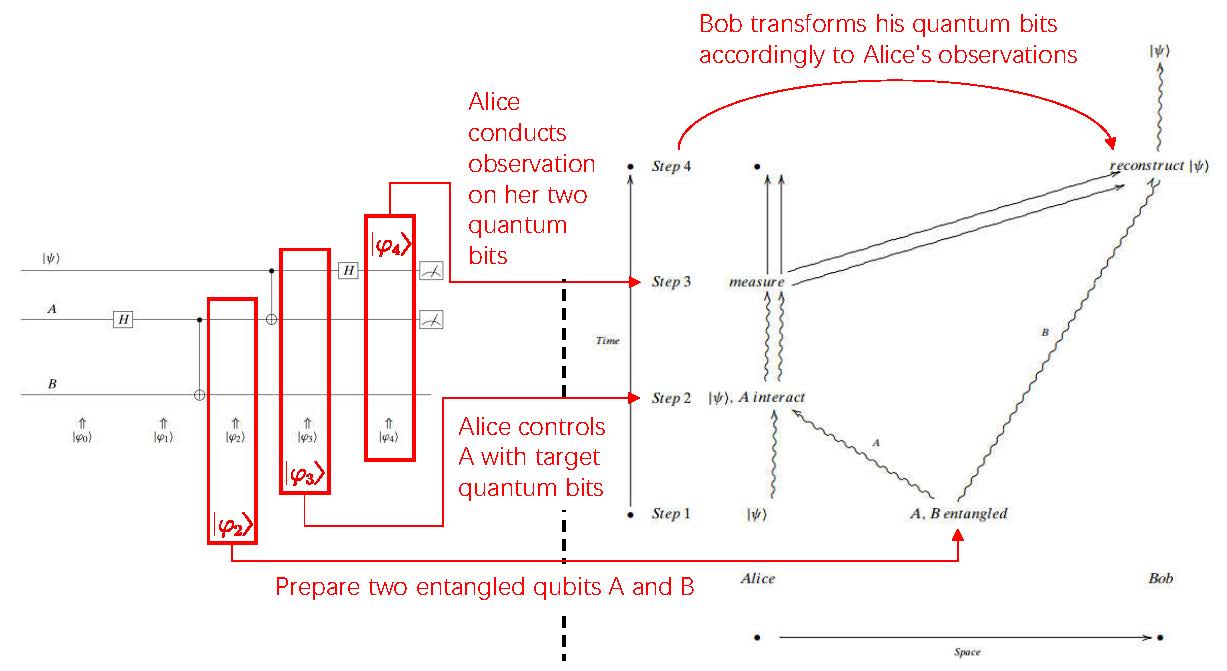

Figure 6.8: The framework of quantum teleportation protocol. Instructor -

The whole framework of the quantum teleportation protocol is shown in Figure 6.8. Several points should be made about this protocol:

-

Alice is no longer in possession of . She has only two classical bits.

-

As we have seen, to "teleport" a single quantum particle, Alice has to send two classical bits. Without receiving them, there is no way that Bob can know what he has. These classical bits travel along a classical channel and thus they propagate at finite speed (less than the speed of light). Entanglement, in spite of its undisputable magic, does not allow you to communicate faster than the speed of light.

-

Information teleported from Alice to Bob via qubit is infinite, but it is useless to Bob once he make the measurement (qubit will collapse to a classic bit).

-

no particle has been moved at all, only the state.

Footnotes

-

The eavesdropper may infer part of the original message from the multiple intercepted ciphertext if the key is reused because ↩